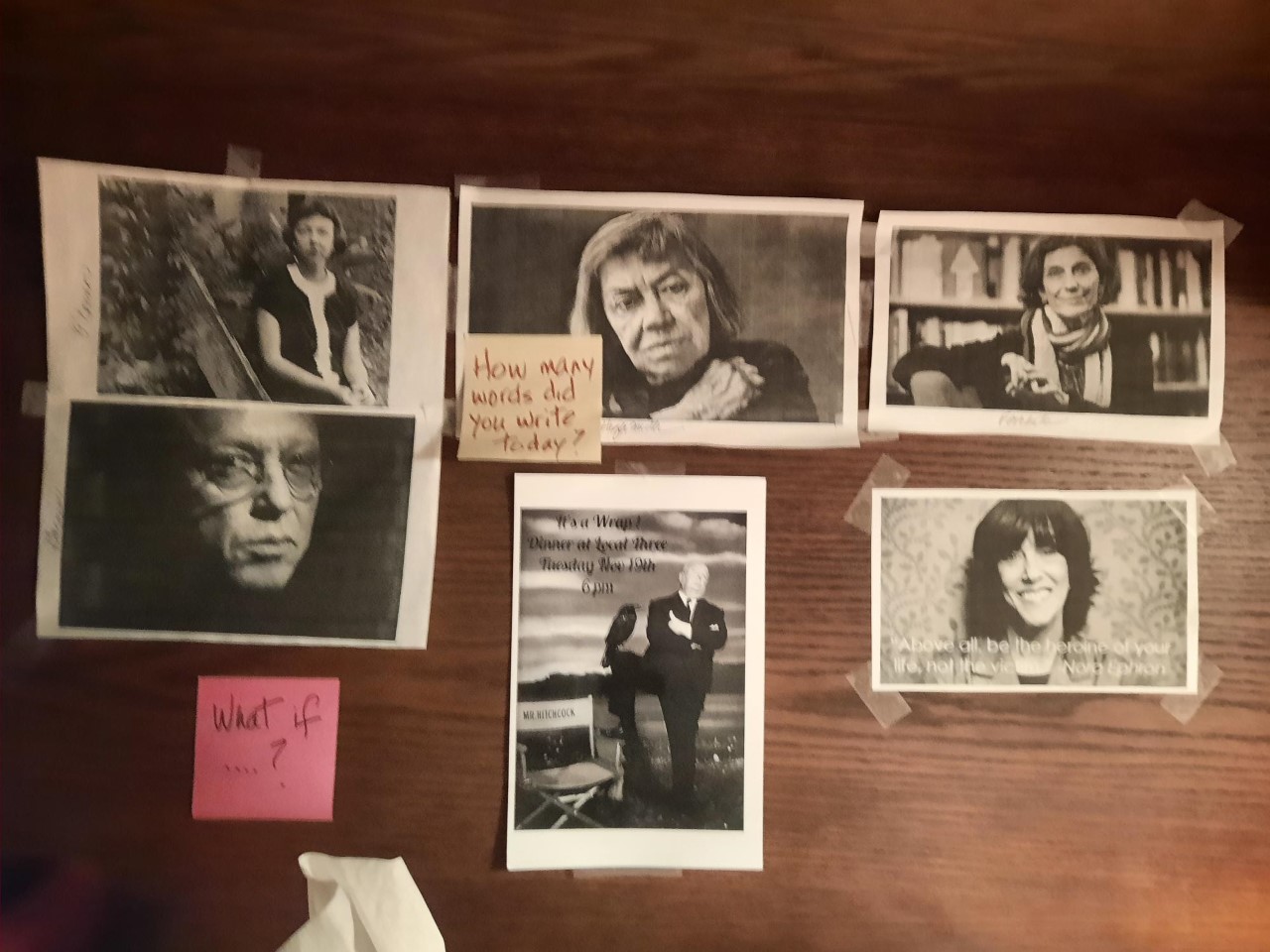

Six photos hang on the wall beside my desk, pictures of my muses. I greet them each morning and request their inspiration, their motivation, and their focus as I turn on my laptop and begin to write. I’d like you to meet them, starting in the upper center of the photos and then going clockwise.

I read my first Patricia Highsmith novel in middle school. After I did a book report on The Talented Mr. Ripley that I’d borrowed from the town library, my English teacher sent a note home to my mother advising her to monitor my precocious literary choices. Over the years I read every Highsmith story I could get my hands on and saw all the filmed adaptations of her books. She introduced me to the world of adult fiction, to psychological insights in purposeful human interactions. Even years after her passing, her stories are fresh, her biography interesting, all worthy of study.

The four thick Neapolitan novels of Elena Ferrante (nee Anita Raja) so engrossed me that I lost track of the days and nights. Restless as I am, most long books are weights on my attention, but this author taught me that less is not always more. I just kept absorbing the 1,693 pages, from the first word of My Brilliant Friend, all the way through the last word of The Story of the Lost Child, when I clutched the book to my heart. She showed me there is no bottom to the depths to which words can transport us.

I’ve watched Nora Ephron’s movies, read her books, enjoyed the down-to-earth self-deprecation I related to as I, like Nora, am a female thrice-married writer. In her movies like Heartburn and Sleepless in Seattle, and her poignant book I Feel Bad About My Neck, she showed me that everyday challenges and problems are worth writing and reading about and proved that humor can rise from the equation of tragedy plus time. I recently re-watched an old Charlie Rose interview with the essayist, author, journalist, screenwriter, and director. They talked about many things, even blogging, and Nora said her blogs are like soap bubbles, about what is true at the moment and not much longer than that. The world is less without her, but we still have her body of work.

Alfred Hitchcock was not an author, but he brought to life stories and screenplays others wrote and turned them into classics. He magnified portrayals of the ordinary man, the likable villain, the MacGuffin, and many engaging devices and ploys to be studied, borrowed, and enhanced. In films like Strangers on a Train, North by Northwest, and Vertigo, he taught me that the clever and the mundane don’t have to cancel each other out.

I’ve read all 12 of Pascal Garnier’s books, each well under 200 pages. They’re a treat on do-nothing days, dark amusements, precursors of reality TV and the Coen brothers’ bloody slapstick. I don’t know how or where I came across the first one I read, The Panda Theory, but his dark absurdities, his borderline possibilities, immediately hooked me on the next and the next. He showed me that truth and fiction can be cohorts, neither being more sacred or silly or sensational or stupid than the other, and that blending them can make for a good read.

I’ve probably read as much about Flannery O’Connor as I have by her and have even visited her home, Andalusia Farm, in Milledgeville, Georgia. I’m ever amazed by this enigmatic woman, steeped in religion and disability and old-timey Southern values, who bared her deepest darkest thoughts and ideas and made me laugh as I simultaneously recoiled in horror while reading stories like A Good Man is Hard to Find. She taught me that we are not what we write, that we don’t have to limit ourselves to writing “what we know”, and that varying perspectives in a story enrich the overall result.

Finally, not hanging on my wall are photos of those in my community of accessible writers, the knowable people who inspire and motivate me and give me deadlines that force me to focus. They show me we’re all in this together with dreams and fears, thrills and tears. We put ourselves out there, naked on the page, and hope our work will inspire others. I am grateful for each and every one of them. And this probably means you’re one of them, because most readers of my blog are writers, too.